The understanding of risk factors associated with COPD has advanced over the last 2-3 decades. Can COPD be considered anymore merely as a smoking disease? Or are there other fires to fight? Summary of the advances was given by Dr Sundeep Santosh Salvi (Pune, India).

Risk factors for COPD: Not all the same

In addition to respiratory symptoms and post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC <0.7, presence of risk factors is essential to reach diagnosis of COPD. Understanding of risk factors has grown over time.

Historical retrospective

The term emphysema was used for the first time in 1821 for hyperinflated lung and thought to be related to air pollution. At the same time, occupational exposure was suspected, e.g. in the glass blowing. In 1950’s, tobacco smoking was shown to be associated with development of lung cancer and heart disease. Chronic bronchitis was linked to air pollution and occupational exposure1,2. A decade later, more evidence was published to show occupational exposures being related to chronic bronchitis and emphysema, later called as COPD3.

Lung function trajectory of smokers

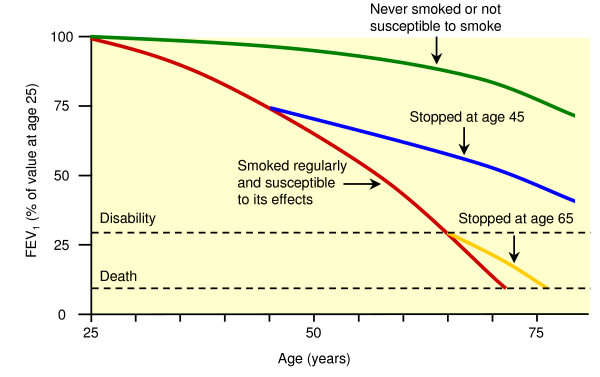

A major advance in understanding the risk factors of COPD came in 1977, when it was shown that smokers had a very rapid and sharp decline in lung function measured by spirometry. The association between tobacco smoking and COPD was established by this study (figure 1.)4

Figure 1. ”Fletcher curve”. Adapted from Fletcher & Peto (1977): The natural history of chronic airflow obstruction

At risk: farmers

In 1987, COPD was concluded to be a work-related disease among farmers, based on data from a 6-year long study with >12 000 farmers from South-Western Finland. Comparing prevalence of COPD in non-smokers, the non-smoking farmers had a higher prevalence (2.7%) compared to the non-farmers (0.7%). Looking at incidence of chronic bronchitis, the regional difference between the agriculturally dense South-west and the North-West was considerable: The south-west region had double the incidence of the North-West (1686/yr. vs <800/yr.)5.

Non-smoking COPD not so rare

Looking at data from almost 13 thousand non smokers over two decades included in the American NHANES study (National Health and Nutrition Evaluation Study, published 1995), about 4% of the men and 5% of women had been diagnosed with COPD, where old age, low income and race could be identified as risk factors6. When Ezzati and colleagues published research of estimates of global, smoking-associated mortality in 2003, they found that more than half of the deaths were attributed to other risk factors7. The 2018 Global Burden of Disease (DALY) linked only 30% of COPD cases to smoking; the remaining 70% were linked to other risk factors, mainly air pollution and occupational exposure. In low-developed countries, COPD cases could include up to 82% nonsmokers8.

Polluted air and open fire cooking

Dr Salvi and his group have conducted studies of respiratory symptoms in the slum population, finding a higher degree of respiratory symtoms compared to the general population9. Looking at prevalence of COPD (confirmed with spriometry) in rural Indian area, proximity to main road fell out as a risk factor along with increasing age, male gender and using biomass fuel for cooking or heating10. However, the risk of COPD may also depend on what the open fire kitchen looks like. A comparison between Indian and Thai women showed that the prevalence of COPD was 5.5 times higher for women in India11. The main contributor for this difference was thought to be the existence of an additional window for ventilation in the Thai kitchen.

Malnutrition

Nutrition plays an important role in developing COPD, according to pooled data from the NHANES study, where a link was made between diet low in antioxidants (Vitamin A, E and selenium) and risk of developing COPD12. Poor nutrition has also been associated with dysanapsis13, which occur early in life and causes a mismatch between airways and lung size (fewer small airways in the lung). Reoccurring respiratory infections may also cause dysanapsis.

COPD, a disease with many etiotypes

The GOLD (2023 and 2024) guidelines14 mention seven etiotypes of COPD, to bring attention to a diversity of risk factors: in addition to COPD -C (C as in cigarettes), we also have the COPD -G for genetics, -D for development (early life events), -P for pollution, -I for infections, -A for (undertreated/childhood) asthma and -U for the unknown etiology of disease. A lot of progress in understanding causes of COPD has been made in the past decades to understand different causes of COPD.

Fight social inequities to improve lung health

Socioeconomic status is a risk factor of COPD. From the global point of view, 55% of COPD is associated with non-smoking risk factors. The risk factors associated with non-smoking COPD include air pollution, asthma, occupational exposure, infections, low lung growth, poor socioeconomic status, dietary factors and genetic factors15. In the high socio-demographic index countries tobacco smoking contributes 70% of total population attributable risk of COPD, making smoking the most important risk to fight.

Countries with low to middle sociodemographic index also have a higher burden of risks: more air pollution, using biomass fuels for heating and cooking, insufficient protection against occupational exposure, availability of asthma medication, dietary factors in addition to socio economic factors. Working to address and reduce the risk factors of COPD, will continue to be important for lung health globally.

Written by

Pekka Ojasalo

Medical advisor, Chiesi Nordic

References

- Doll R, Hill AB. Smoking and Carcinoma of the Lung. BMJ. 1950 Sep 30;2(4682):739–48.

- Fairbairn AS, Reid DD. Air pollution and other local factors in respiratory disease. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1958 Apr;12(2):94-103. doi: 10.1136/jech.12.2.94. PMID: 13546576; PMCID: PMC1058697.

- Phillips AM. The influence of environmental factors in chronic bronchitis. J Occup Med. 1963 Oct;5:468-75. PMID: 14072846.

- Fletcher C, Peto R. The natural history of chronic airflow obstruction. Br Med J. 1977 Jun 25;1(6077):1645-8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6077.1645. PMID: 871704; PMCID: PMC1607732.

- Vohlonen I, Tupi K, Terho EO, Husman K. Prevalence and incidence of chronic bronchitis and farmer’s lung with respect to the geographical location of the farm and to the work of farmers. Eur J Respir Dis Suppl. 1987;152:37-46. PMID: 3499345.

- Whittemore AS, Perlin SA, DiCiccio Y. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in lifelong nonsmokers: results from NHANES. Am J Public Health. 1995 May;85(5):702-6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.5.702. PMID: 7733432; PMCID: PMC1615439.

- Ezzati M, Lopez AD. Estimates of global mortality attributable to smoking in 2000. Lancet. 2003 Sep 13;362(9387):847-52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14338-3. PMID: 13678970.

- Global Burden of Disease Report, 2018

- B. Brashier, J. Londhe, S. Madas, V. Vincent and S. Salvi, ”Prevalence of Self-Reported Respiratory Symptoms, Asthma and Chronic Bronchitis in Slum Area of a Rapidly Developing Indian City,” Open Journal of Respiratory Diseases, Vol. 2 No. 3, 2012, pp. 73-81. doi: 10.4236/ojrd.2012.23011.

- Ghorpade D, Agarwal D, Juvekar S, Salvi S. Residential proximity to main road and the risk of COPD. Lung India. 2022 Nov-Dec;39(6):588-589. doi: 10.4103/lungindia.lungindia_224_22. PMID: 36629243; PMCID: PMC9746278.

- S. Salvi, T. Khansamrong, S. Madas (Pune, India). Prevalence of COPD by different types of cooking fuel between India and Thailand. Eur Respir J 2010; 36: Suppl. 54, 2570 (Poster)

- Liu Z, Zeng H, Zhang H. Association of the oxidation balance score with the prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease from the NHANES 2007-2012: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Heart Lung. 2024 Mar 5;65:84-92. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2024.02.005. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 38447328.

- Smith BM, Kirby M, Hoffman EA, et al. Association of Dysanapsis With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Among Older Adults. JAMA. 2020;323(22):2268–2280. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6918

- GOLD 2023 and 2024 reports

- Yang IA, Jenkins CR, Salvi SS. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in never-smokers: risk factors, pathogenesis, and implications for prevention and treatment. Lancet Respir Med. 2022 May;10(5):497-511. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00506-3. Epub 2022 Apr 12. PMID: 35427530.

ID7385-19.03.2024